Mini clothespin may give safer way to fix leaky valves without open-heart surgery, study says

By Marilynn Marchione, APSunday, March 14, 2010

Study: Mini clip is safer than heart-valve surgery

ATLANTA — Many Americans with leaky heart valves soon might be able to get them fixed without open-heart surgery. A study showed that a tiny clip implanted through an artery was safer and nearly as effective as surgery, doctors reported Sunday.

The device is already on sale in Europe, and its maker, Abbott Laboratories, hopes to win approval to sell it in the United States next year. Elizabeth Taylor reportedly got one last fall — the 77-year-old actress told fans about it on Twitter.

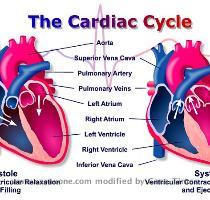

About 8 million people in the U.S. and Europe have leaky mitral valves — the valve between the heart’s left upper and lower chambers. Not all are so bad they need treatment, but the worst cases can lead to heart failure over time.

In the study, six times more people who had surgery suffered complications during the next month than those who got Abbott’s MitraClip. Deaths, strokes and blood transfusions were less common with the device. The clip was not dramatically less effective than surgery after one year.

Doctors called the study a watershed — the first big test of repairing or replacing heart valves through arteries rather than drastic surgery.

The MitraClip is only for the mitral valve. Other devices for other heart valves are in late-stage testing, and many doctors believe they will transform how these conditions are treated in the near future.

“We have opened the door for a new therapeutic option for patients,” said Dr. Ted Feldman of NorthShore University Health System in Evanston, Ill.

He led the new study and gave results Sunday at an American College of Cardiology conference. The study was sponsored by Evalve Inc., which developed the device. Evalve was sold last year to North Chicago, Ill.-based Abbott, and Feldman consults for the firm.

Some surgeons were not convinced the device is close to surgery’s effectiveness, and said patients need to be studied for more than one year.

“It’s a partial victory for the device,” Dr. James McClurken, a surgeon at Temple University in Philadelphia, said of the result. McClurken also is the conference chairman.

The study used an outdated method of surgery that minimizes its true benefit, said Dr. J. Scott Millikan, a surgeon at the Billings Clinic in Montana.

“Clearly this is a very exciting technology,” but the study’s leaders “set the bar for success way too low” for the device, he said.

The mitral valve is like a saloon door that opens to let blood flow into the heart’s main pumping chamber. When the flaps of the door don’t swing completely shut, blood flows back into an upper chamber of the heart.

Medicines can ease symptoms but do not keep the valve problem from getting worse. Bad cases are treated with open-heart surgery: Doctors partly stitch the flaps together in the middle, allowing blood to flow on either side but keeping them aligned during each heartbeat.

The MitraClip imitates those stitches. With the patient under general anesthesia, doctors push a tube into a blood vessel in the groin and guide it into the heart. The device, a fabric-covered metal clothespin, is mounted on the end of the tube and clips the two flaps of the valve together.

In the study, 184 people were assigned to get the clip and the procedure was successful in 136. Major complications occurred in 10 percent of people treated with the clip compared with 57 percent of 79 other patients treated with surgery. Two surgery patients died, two suffered major strokes, and four needed emergency heart surgery; none of the clip patients had those problems.

That made the device much safer than surgery, researchers said.

As for effectiveness, the study was only designed to see if the device was not substantially inferior to surgery and by that measure, it passed.

After one year, valve problems were sufficiently resolved in 72 percent of device patients and 88 percent of surgery patients.

Surgery is better, “but it’s not so much better that patients, given the choice, want to undergo the open-heart procedure,” especially given the difference in safety, Feldman said. “Part of what makes this attractive is that when the clip doesn’t work, surgery remains an option,” so the less drastic treatment could be tried first, he added.

The results are “very enticing and very exciting,” although longer-term study is needed, said Dr. Robert Bonow, a former American Heart Association president and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

“The surgeons would argue this is less good of a result. But from the patient’s point of view, this might be exactly what you need” to turn a big problem into a mild one that does not need further treatment, Bonow said.

Dr. Donald Glower, a Duke University cardiac surgeon who co-led the study, agreed.

“This is part of the trade-off we have” with many treatments that avoid surgery. “It’s probably not realistic” to expect it to be as good, he said.

No price for the device has been set in the U.S., but it sells for about $27,000 in Europe, plus whatever doctors and hospitals charge to implant it — as yet unknown.

“You have to look at it always in comparison to the alternative” — valve surgery costs $50,000 or more, including a longer hospital stay, said John Capek, executive vice president of Abbott’s medical devices division.

On the Net:

Cardiology meeting: www.acc.org

Tags: Atlanta, Diagnosis And Treatment, Duke, Georgia, North America, Surgical Procedures, Twitter, United States