Study: Bone drugs Fosamax, Reclast prevent far more fractures than rare breaks linked to them

By Marilynn Marchione, APWednesday, March 24, 2010

Study adds evidence that bone drugs work, are safe

A new study gives reassuring news about the safety of Fosamax and Reclast, bone-building drugs taken by millions of American women. It found that long-term use does not significantly raise the risk of a rare type of fracture near the hip.

On balance, these drugs prevent far more fractures than any they may cause when used to treat the bone-thinning disease osteoporosis, said the study’s leader, Dr. Dennis Black of the University of California, San Francisco.

“If we treated 1,000 osteoporotic women for three years, we estimate you would prevent 100 fractures,” at a possible cost of one or fewer of the unusual bone breaks examined in this study, he said.

Results were published online Wednesday by the New England Journal of Medicine.

Lots of older people, especially postmenopausal women, take these drugs, called bisphosphonates. They range in cost from $100 for a three-month supply of the generic version of Merck & Co. Inc.’s Fosamax pills to as much as $1,200 for an infusion of Novartis AG’s Reclast, given as an annual infusion. Other brands are GlaxoSmithKline PLC’s Boniva and Warner Chilcott PLC’s Actonel.

Studies show they lower the risk of spine and hip fractures, which can be debilitating and often lead to a downward spiral and death in the elderly.

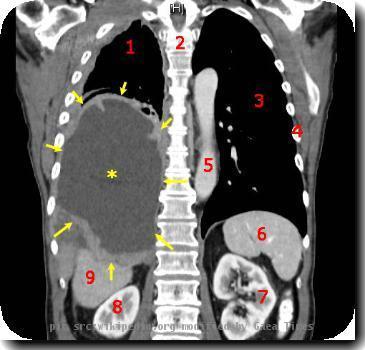

The drugs are widely considered safe. However, some case reports have tied them to unusual fractures of the upper thigh bone, just below the hip, that seem to occur without provocation or injury.

Patients “just step, they hear a crack, and they suffer a fracture,” Black said.

To study this risk, researchers combined results from three large studies involving more than 14,000 women who were given Fosamax, Reclast or dummy treatments for three to 10 years.

In all, 284 hip and leg fractures occurred, including 12 of the unusual upper-thigh type. There was a trend toward more of these unusual fractures among bisphosphonate users, but the difference was small enough to have occurred by chance.

This is reassuring, although the study cannot rule out risk, Black said.

“There are too few fractures for definitive proof. But what it does show is that these are very, very rare,” he said.

The study was sponsored by Merck and Novartis. Several authors work for the companies, and others consult for them or other makers of osteoporosis treatments.

Other reasons the study cannot completely rule out risk is that not many participants took the drugs longer than three years and many took a lower dose of Fosamax than is commonly used now, Dr. Elizabeth Shane of Columbia University writes in an editorial in the journal.

Still, the results show that “many more common and equally devastating hip fractures are prevented by bisphosphonates than are potentially caused by the drugs,” she concludes.

Shane is co-leader of an expert panel for the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research that is evaluating the risk of these unusual fractures. Her university has received research grants from drugmakers but she has no personal financial ties to any.

The safety of bisphosphonates may take on even more interest in the future: Two recent studies hint that these drugs might help prevent breast cancer. The cancer studies are not definitive — better ones are under way now, and should give an answer in a year or two. Any safety concerns could dampen enthusiasm for wider use of this class of drugs.

On the Net:

New England Journal: www.nejm.org