Even at the Super Bowl, there’s new talk about increased concussion awareness in the NFL

By Tim Reynolds, APThursday, February 4, 2010

Concussion awareness grabbing hold across the NFL

MIAMI — Anthony Hargrove has endured plenty of concussions. The exact number, that’s a mystery.

Even to him.

“I don’t really worry about them too much,” said Hargrove, the New Orleans defensive lineman.

For years, that was consistent with the thinking around much of the NFL, perhaps around football in general. Not anymore.

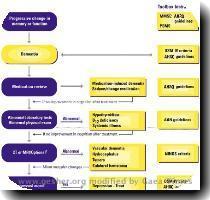

This season, concussions and their aftereffects became a theme across the league, a once-taboo topic brought forward as researchers found more evidence of a link between concussions and dementia, the league adopted new policies about player clearance, and lawmakers took up the issue. Thirty of 160 NFL players surveyed by The Associated Press in November even came forward to say they had hidden or played down the effects of a concussion.

In the buildup to the Super Bowl, brain injuries have been a talking point again.

“I’m very aware of the players of yesteryear who are struggling physically, mentally, so it’s a very serious deal,” Indianapolis quarterback Peyton Manning said. “I think current players are realizing just how serious.”

Still, finding out how many concussions players in the title game have had, well, that’s about as easy as getting teams to divulge their game plan for Sunday night’s matchup.

“Only two major ones,” said Saints backup quarterback Mark Brunell.

“I think none in my NFL career,” replied Colts linebacker Gary Brackett.

“Every player probably has, at some point,” offered Saints wide receiver Marques Colston.

Hargrove is believed to be the New Orleans player with the most concussions over his career, though he made it through this season without adding to that total. On the Indianapolis side, the leader could be tight end Dallas Clark, who has been diagnosed with at least four in his NFL days, possibly five, possibly more.

He won’t say.

“I’m not shocked at all,” said Dr. Gillian Hotz of the University of Miami, who has studied brain injuries extensively. “What happens is, they build up this sensitivity that it’s OK to have these headaches all the time, that it’s OK to be a little dizzy, it’s OK that their vision’s blacked out. It goes away and they just keep playing, and the next time, it happens faster and the headaches last a little longer.”

Dan Federkeil wouldn’t disagree with her assessment.

The Colts’ offensive tackle is 6-foot-6, 290 pounds, strong and tough. He won’t be playing in the Super Bowl because of lingering aftereffects of his third “major” concussion, two of those coming in the past two years.

The definition of “major” varies a bit when talking about brain injuries. In Federkeil’s case, he’s entering his fourth month of headaches, and doesn’t know what it will mean for his football future.

“I’ve never really had any issues with vision or balance,” Federkeil said. “My biggest issue’s been headaches. It just tests your patience like nothing else. Last time it was a throbbing, all-day (pain). This time it’s sharp pains, they come and go, you never know when they’re going to come.”

In November, the NFL sent a memo to all 32 teams, with commissioner Roger Goodell saying he would consider potential rule changes “to reduce head impacts.” Around the same time, Ben Roethelisberger and Kurt Warner — the two quarterbacks from last year’s Super Bowl — each needed to take the same week off because of concussion-releated problems. Tests on new helmets are also been conducted to see if they would make the game safer, with some concrete data on that front expected next month.

The culture, it seems, may be changing.

About time, said retired NFL star Rod Woodson, who’s working the Super Bowl for NFL Network.

“More is being done today than it was 20 years ago, so it’s a good thing. It’s a positive sign,” Woodson said. “Only time tells. It’s hard to say what’s going to happen 20 years from now. But I think the key thing is that the players, I guess, are more vulnerable or more willing to give out information. In the old days, players would say, ‘I’m not hurt’ and they were dinged up for a quarter and a half.”

There’s a simple reason why some players won’t say when they get hurt, “nicked” or “dinged” in a game.

They can lose their job that way.

And in the Super Bowl, even a Pro Bowl linebacker such as New Orleans’ Jonathan Vilma said it’d be tough for anyone to willingly come off the field.

“It’s the player’s job to play football. That’s what we do for a living,” Vilma said. “The trainers and the head coaches, it’s their job to understand what’s best for the player. Of course, the player’s going to say, ‘I don’t know when this opportunity’s going to come back, so I want to play.’”

Injuries are unavoidable in the NFL, and on every sideline, someone is there waiting to take a spot on the field. Some might say playing through being woozy for a couple plays is a sign of toughness, some might say a sign of silliness, but that’s the way of life in just about all levels of football.

“I thought I just got my bell rung,” said the Saints’ Scott Shanle, who played through a concussion this season against Dallas. “The next day I had more headaches than usual and my balance was not right. I told the team and the first thing they said is, ‘You’re not going to try to do any practice.’ At that point I knew I was going to miss that week.”

Some players can’t believe more of their colleagues aren’t sidelined longer.

Colston was asked this week to describe what being on the receiving end of an NFL hit is like. He thought a minute before giving his answer.

“To me, it’s the equivalent of a car accident,” Colston said. “You definitely appreciate, as a player, all the research that’s going into it now and the situation being brought to the forefront. A lot of guys, when they’re playing, they don’t think about the long-term effects. I think it’s important to learn that stuff.”

Hotz said she believes progress is finally being made, at all levels of the game.

Just this week in Miami, a call for legislation was made, asking all 50 states to minimize the possible complications after brain injuries by requiring kids suspected of having concussions to get written consent from a doctor before returning to competition.

Said Woodson: “Players are starting to realize how important it is to take care of your brain. You only get one of them.”

AP Sports Columnist Jim Litke and AP Sports Writers Steven Wine and Brett Martel contributed to this report.